Gloomy tombs and morbid mummies? Everyday Egypt was much more than that, argues Richard Parkinson in a first glimpse of a new series focusing on the ancient world, free with tomorrow's Guardian

- Richard Parkinson guardian.co.uk,

- guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2010

Ancient Egypt rarely escapes our stereotypical view of it: an exotic place full of pyramids crammed with cursed treasure, waiting to be discovered by adventurous archaeologists. As in René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo's comic Asterix and Cleopatra, it is often presented as a land of spooky tombs and people speaking in hieroglyphic pictures. These stereotypes are themselves quite ancient – even to the ancient Greeks, Egypt was a quintessentially different culture. But they trivialise a complex society.

Ancient Egypt is one of the first civilisations that children are taught about, and so people sometimes assume that it must be a "childish" culture, an early step in humanity's evolution towards modernity. People of all ages visit the displays of mummies in the British Museum, and there can be no more vivid way of stirring anyone's historical imagination than to look into an actual ancient face. But as we stare, we can sometimes forget that they were more than mummies, and that once they were people as complex and sophisticated as us.

Some of our misunderstandings about ancient Egypt come about in part because the Egyptians presented much of their history in a monumental and monolithic form. For centuries, the Egyptians codified in stone their history as a list of kings, each the son of the sun god, each a triumphant hero who, with each reign, re-established order in a chaotic universe. Even now, Egyptian history is conventionally divided into great kingdoms of centralised rule, the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms, divided by periods of supposed chaos. The central role of the king is perhaps the key to Egypt's self-representation: every king re-established Egyptian society, eternal and unchanging since the time of the gods.

In these official records, Egypt presented itself as an extremely conservative culture. As in any society, it is all too easy to accept this ideology at face value, but there were huge changes behind this facade and continual tensions between the royal centre and periphery – aspects of history that were written out of royal inscriptions. After so many centuries, how can we get behind these official political pronouncements and begin to understand the Egyptians in context?

Occasionally we have different types of evidence for the same events, which allow us a fuller picture. In 1858BC at Semna, in Nubia at the southern edge of Egypt, King Senusret III erected an inscription to mark the border of his territory. In this, he proclaimed scornfully that the Nubian locals "only have to hear and then fall at a word: just answering them makes them retreat". But the archaeological context reveals that the inscription was erected in a massive mud-brick fortress, which shows that the king needed more than words to control the Nubians. And this fortress was part of an expansion into Nubia that was motivated by complex economic and political factors. The history of the area was not simply a triumph of royal rhetoric.

For one week during the reign of the following king, Amenemhat III, we have evidence that hints at a more complex history underlying this monumental facade. A fragmentary series of military despatches records trivial realities such as the arrival of a group of soldiers to report "on month 4 of winter, day 2 at breakfast-time" that a patrol had returned with the news that "we found the tracks of 32 men and three donkeys". This was a civilisation not just of pyramids, but also petty paperwork and interrupted breakfasts.

The ancient Egyptians were, of course, as fully aware as any modern historian or politician of the difference between words and reality. The dichotomies between what one can say on an official monument and what one really feels is vividly conveyed in a letter from Luxor, dated around 1100BC, in which the pharaoh's general Payankh tells a scribe to have two troublesome policemen "put in two baskets and thrown into the water by night – but don't let anyone find out". He continues: "and Pharaoh (life, prosperity, health!) – how will he even get to this part of the land? And ... whose boss is he anyway?" Such dissidence is unthinkable in Egyptian official writings, although even here the writer adds the obedient salutation to the Pharaoh's health even as he mocks him.

Life and death

Boris Karloff in the 1932 motion picture The Mummy Photograph: © Bettmann/CORBIS

Boris Karloff in the 1932 motion picture The Mummy Photograph: © Bettmann/CORBIS Popular books often tell us that the ancient Egyptians spent their whole life preparing for death. Western cinema has been haunted by the image of the mummy emerging from its tomb to send innocent westerners to their doom ever since Boris Karloff appeared as the bandaged Imhotep in 1932. But if we read Egyptian poetry, we find that their attitudes to death were more complex. Poets lament the cruelty of death, and urge their readers to enjoy life: "Follow the happy day! Forget care!"

Because cemeteries were located in the desert, they are better preserved than anything else, and this has given us a very distorted view of the culture – imagine if only municipal cemeteries were preserved from Victorian Britain.

Yet they can still tell us as much about life as death – the dry desert can preserve organic material so well that we can still handle actual wigs, baskets, food and flowers from 3,000 years ago. Objects from a person's life were buried with them in the tomb, and when we can still see a baker's fingerprints in an ancient loaf of bread we sense some of the material experience of their lives better than from any inscription.

But even here there is a danger: tombs filled with such variety tell us only about the lives of those who could afford to be buried this way – that is, the wealthy elite.

Gossip and swearing

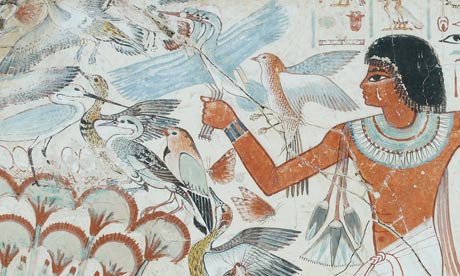

Scenes inside the tombs themselves defy the cliches: the modern visitor is often shocked to find how intimate and colourful a place they are. They show workmen squabbling and fighting among themselves, very much alive. And when we can observe the ancient Egyptians' own interactions with their dead, they were usually not concerned with magic or curses as we might expect, but with more immediate domestic matters. People would visit tomb-chapels and sometimes write letters to their dead relatives, asking them for help with ongoing family problems. In one example, a husband asks his dead wife why she is persecuting him from the underworld, repeatedly protesting (perhaps rather too much) that he had never done anything with the serving girls. The blessed dead were still part of the living family even when they had left the land of the living.

Deir el-Medina, Egypt - Ancient mudbrick walls crumble in the desert west of the Nile River at Luxor, Egypt Photograph: Roger Wood/CORBIS

Deir el-Medina, Egypt - Ancient mudbrick walls crumble in the desert west of the Nile River at Luxor, Egypt Photograph: Roger Wood/CORBIS Much less survives from settlement sites because they were almost always in the agricultural land of the Nile valley. Luckily for us, there are a few exceptions, such as the village of the craftsmen who decorated the royal tombs in the Valleys of the Kings and Queens, now known as Deir el-Medina, in the 1200sBC. For reasons of convenience, this was built near their workplace in the desert hills, and so it preserves a unique range of archaeological and textual material. In Deir el-Medina we can still see and study their living spaces, their furniture and vast quantities of discarded broken pottery. We can also still read about the minutiae of daily life: the problems of donkey hire, and accusations of sleeping around ("he had sex with the lady Hel while she was married to Hesysunebef … and when he'd had sex with Hel he had sex with Webkhet, her daughter. And then Aapehty, his son, had sex with Webkhet"). We can see universal human concerns embodied in very different cultural ways from our own: government–employed artists drew cartoons in which animals parody the official art they produced for the kings – a mouse pharaoh in a chariot attacks a citadel of cats, imitating scenes of royal victories. This one small village gives us evidence for a full range of human intrigues, gossip, learning, sophistication and sensuality that is mostly lacking in our record of Egypt's long history. In Deir el-Medina it is impossible to forget that these ancient people were once very much alive.

Egyptology is a relatively recent discipline, and was born in imperial times. Unfortunately it is still tainted by its own colonialist stereotypes or those similar to the macho archaeologist embodied by Indiana Jones. Popular books still go on relentlessly about uncovering finds, cracking secret codes – a language that implies that we are acquiring hidden treasures and bringing them from primitive darkness into modern scientific light. Real Egyptology, however, is no longer about acquiring objects, but about understanding their meaning in their original context, and about working within the Egyptian landscape. Long gone is the old colonial arrogance that once denied to ancient Egyptians any possibility of being our equals – and denied to modern Egyptians any interest in their own culture: Egyptology is now always a partnership with modern Egypt. More sophisticated theoretical perspectives are developing, drawing on work from other disciplines, and we are beginning to understand Egyptian culture more as a whole, and less as a sequence of facts and artefacts. Our European stereotypes are not the only way of viewing this past, no matter how familiar and natural they seem to us. Modern scholarship has a lot to learn from how modern Egyptians have engaged with their history: when the Egyptian director Shadi Abd al-Salam filmed the story of a 19th- century discovery of royal mummies, his film was titled The Mummy – but instead of being another crude yarn of monsters and curses, it sympathetically explores our complex relationship with this ancient heritage, and reminds us that ancient and modern Egypt are parts of the same country.

Culture shock

When we encounter an ancient Egyptian artefact face to face, it often produces a strangely mixed feeling of meeting something very different from our own culture, but also very familiar. No matter how "other" it is, it can also give us a slight shock of recognition.

And sometimes not so slight. It is said that when the statue of the aristocratic lady Nofret from c2600BC was first discovered in 1871, the workman excavating the chamber ran out of the tomb, terrified. He had tunnelled into a chamber and looked through the hole to find he was looking straight into the statue's eyes, inlaid with rock crystal, which seemed to be staring back at him. The excavator, Albert Daninos, described the eyes as "uncomfortably real".

Which is exactly the point: when we look at the ancient world, we do not expect the ancient dead to look back at us, or to look so lively. We prefer them to stay safely dead, distant and irrelevant. "Uncomfortably real", the ancient Egyptians can still challenge our assumptions that ours is the only way of looking at the world, and remind us that they saw it differently.

Richard Parkinson is a curator in the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan at the British Museum. His main research interest is the poetry of the classical age of Egyptian literature

No comments:

Post a Comment